Recently, several riders have brought oil-starved bikes into the shop–whether they were new riders or simply neglected to check their oil level for too long, the results have been uniformly disastrous. Motorcycle engines tend to rev high and hot, and like other internal combustion machines, an engine’s metal-to-metal contact points need a consistent film of oil lubrication between moving parts, whether those parts are bearings, camshafts, or piston and cylinder. When the oil level drops below a certain level, it spells certain doom for the bike’s motor–possibly with terrible consequences for the rider. In this case, the V-Strom’s owner ignored the low oil light for approximately 2,000 miles before the bike “began to make a terrible rattling noise” and breathed its last. The unmistakable rattling noise and the sparkling bits of metal in the oil confirmed to us that the motor was in bad shape. Turned out that the engine was damaged beyond repair; we found a replacement engine and installed it, and the rider learned an expensive lesson in responsible bike maintenance.

Riders–remember to check your oil level and keep your bike filled to the appropriate level! The engine is the heart of a bike, and oil is its lifeblood.

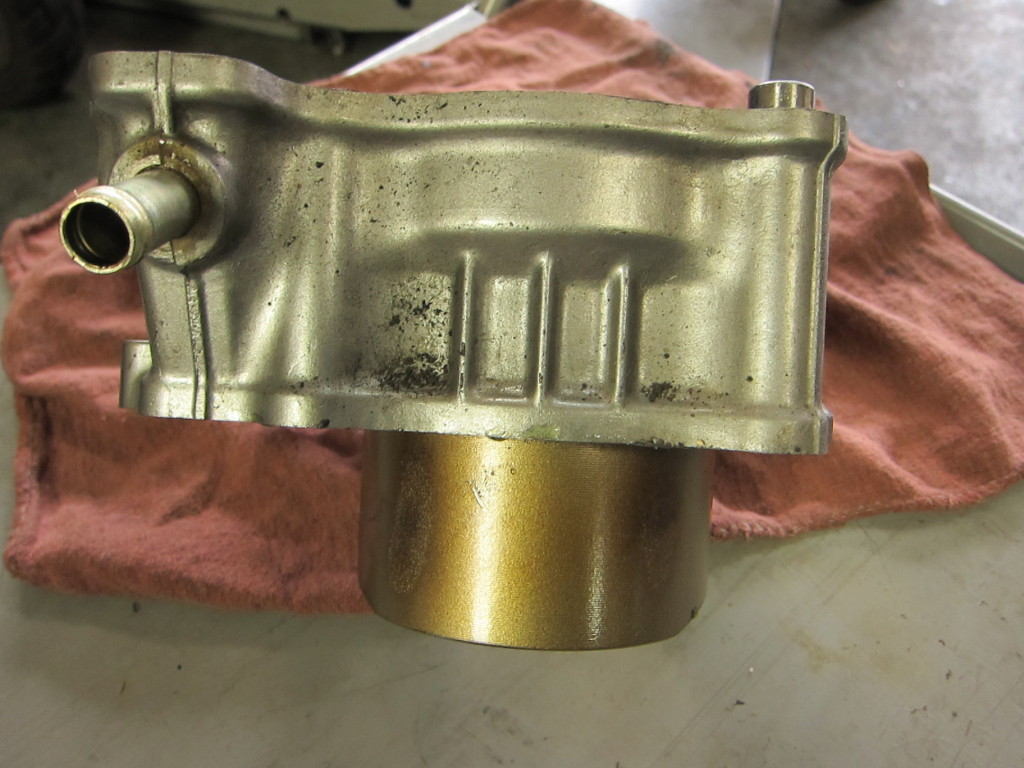

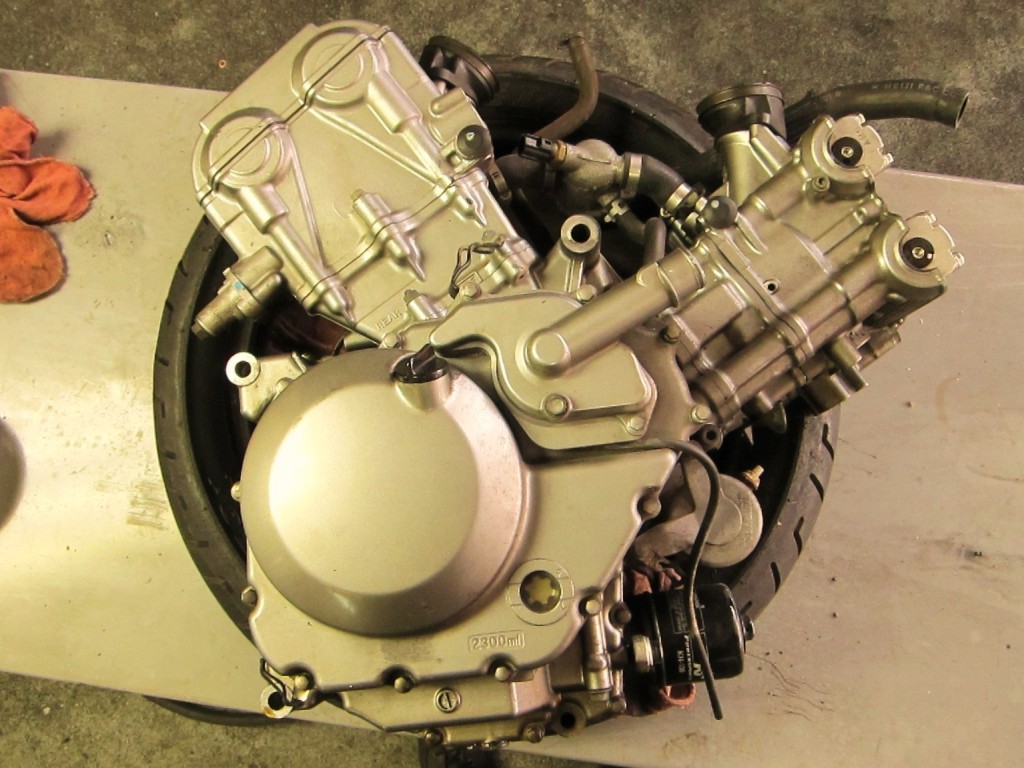

The engine from a 2007 Suzuki V-Strom 650--the same bike featured in the oil change tutorial This one, however, was ridden by its uninformed owner until it was dry of oil

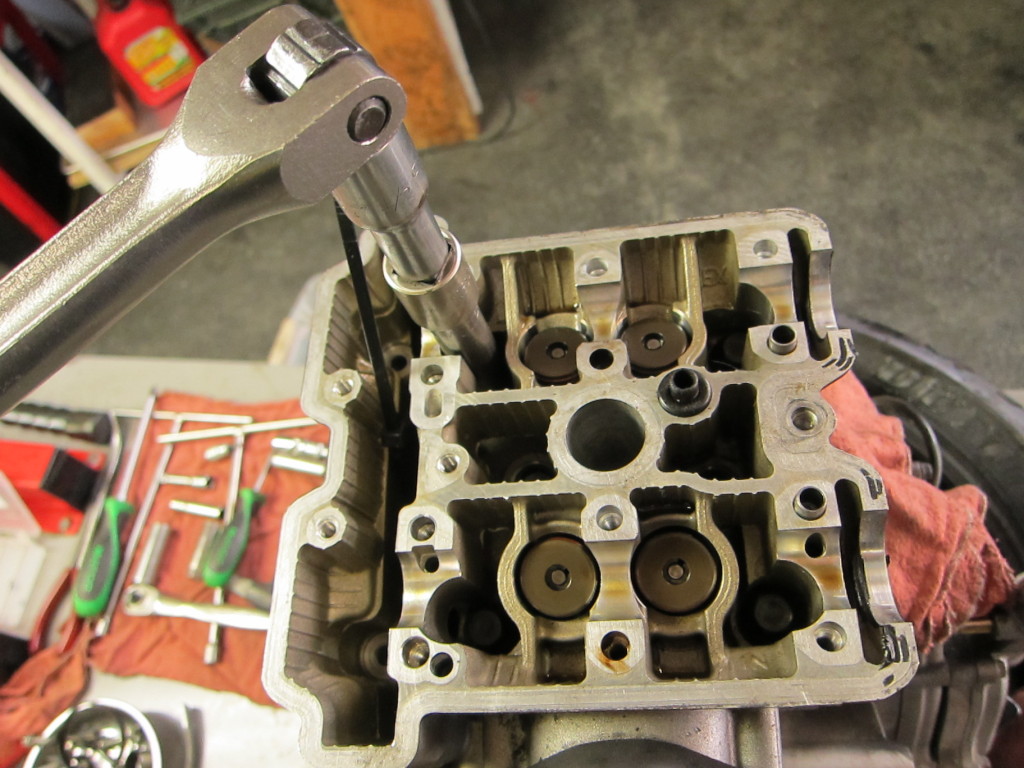

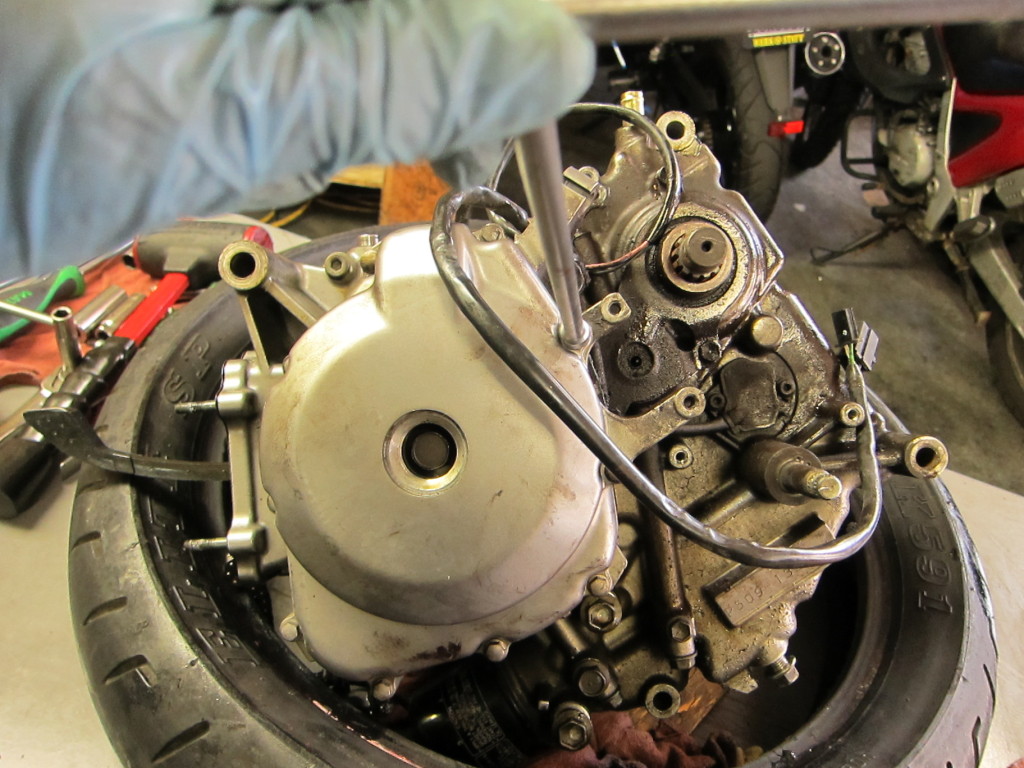

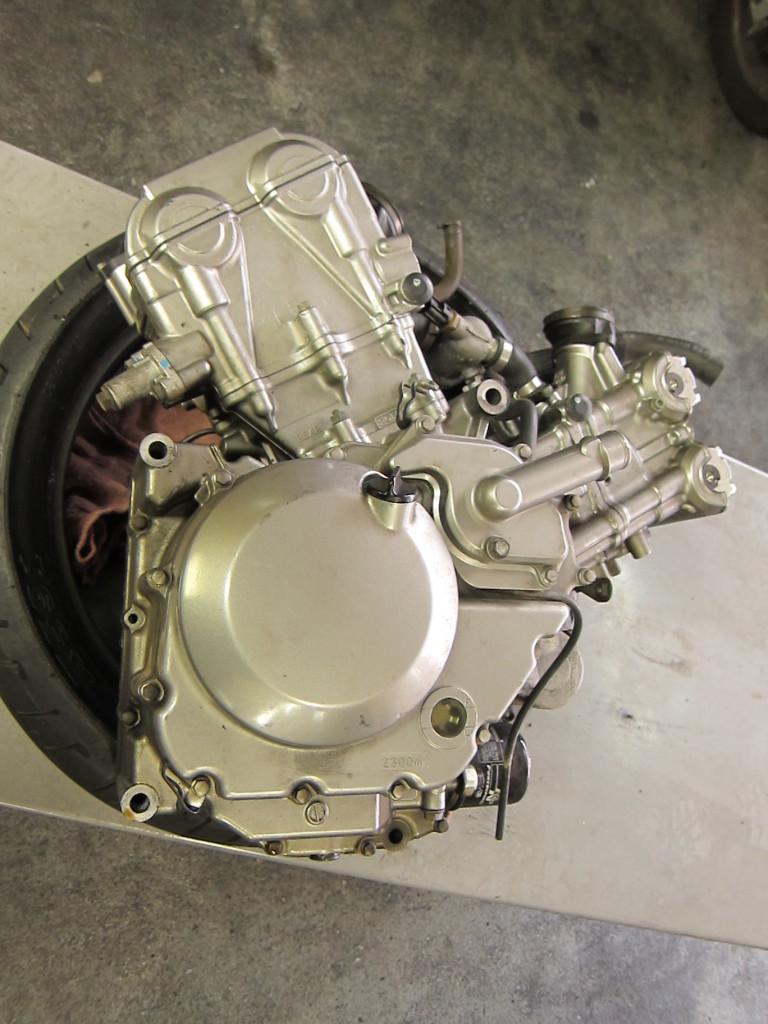

Another view of the V-Strom engine--note that the front cylinder has already had its valve cap removed in an effort to diagnose the problem.

It’s painful but fascinating to dig into a ruined engine like this and do a sort of autopsy to discover which parts failed. This is the normally very robust vee-twin engine on the lift, ready for disassembly. It’s a messy, dirty job, so I’ve got gloves on and plenty of rags and a pan on hand to catch spills.

First I loosened the bolts and eased out the starter motor.

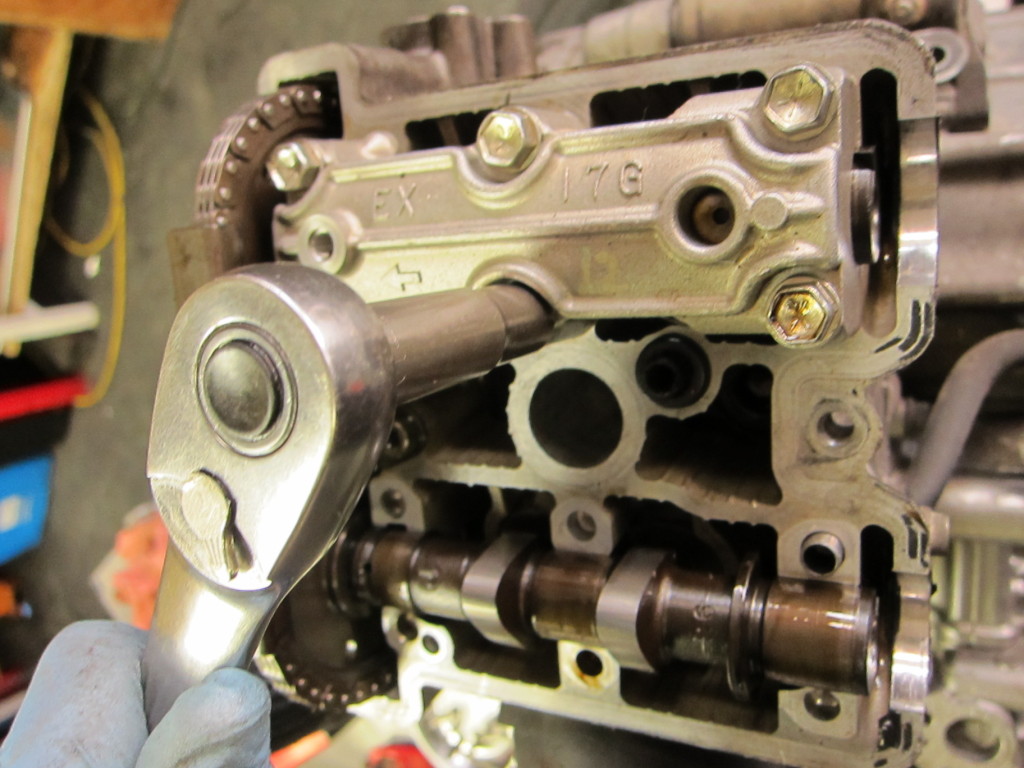

Next, off came the valve cap on the forward cylinder head, and then I removed the camshaft journal covers. In both cases, the caps should be removed in a star pattern to prevent the aluminum from warping as it is removed.

In order to loosen the cam chain and remove the camshafts, the cam chain tensioner needs to come off first.

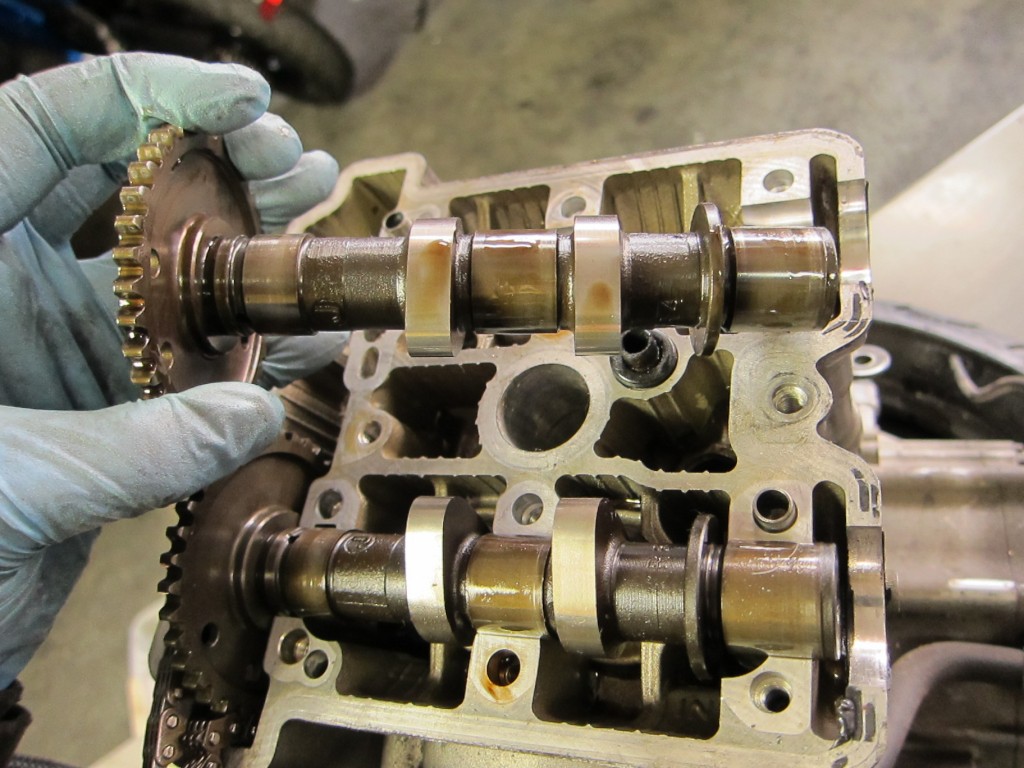

At this point, the camshafts are exposed, and the cam chain is loose and can be pulled off, releasing the camshafts. The cam lobes, which rotate and push the valves open and closed, are vulnerable when the bike’s oil runs dry, as are the camshaft journals, which turn inside their bearings in the engine head. Upon inspection, though, the entire surface of both the intake and exhaust camshafts showed no evidence of wear or galling, a testament to the toughness of the V-Strom engine.

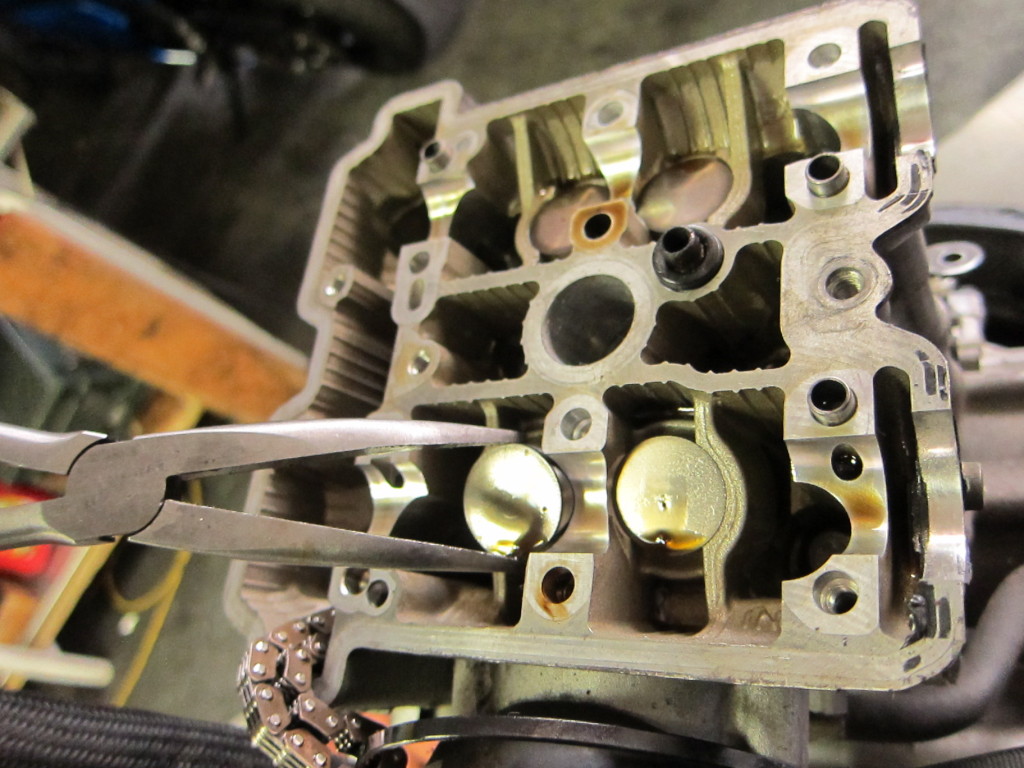

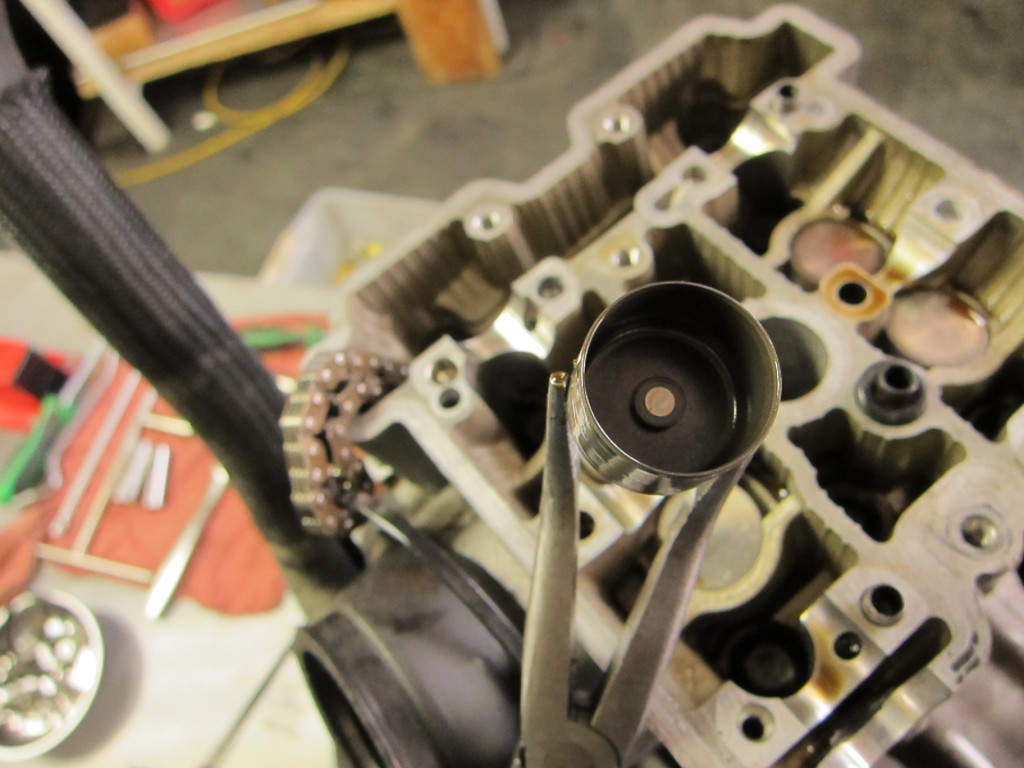

With the camshafts removed, the valve tappets (or buckets) are exposed, easy to pull with a pair of needlenose pliers or a magnet. Since the V-Strom uses a shim-under-bucket valve design, each shim sits on the underside of each tappet. The small shims require care and a deft hand to avoid dropping into the engine, a bad scene if you’re doing a valve adjustment.

Generally, as here, the small shim adheres to the underside of its tappet, and comes out with it.

With the camshafts, tappets and shims gone, the valve ends and the tops of the valve springs can be seen.

The head bolts came out next–that took a breaker bar.

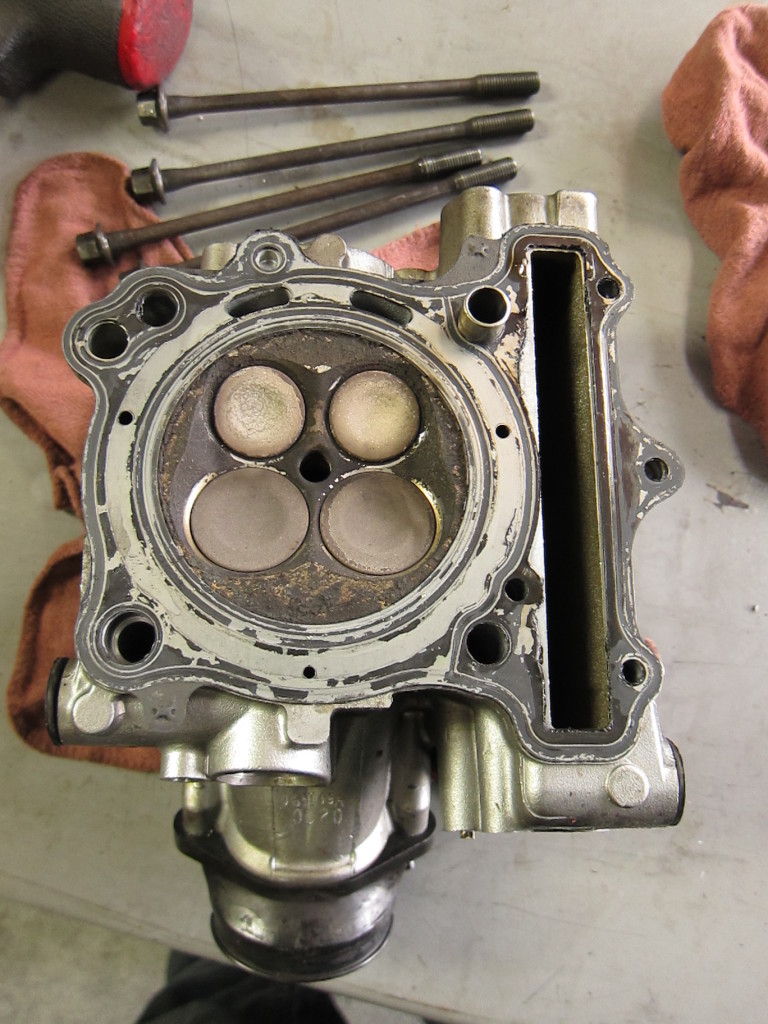

The intake and exhaust valves showed no obvious signs of being bent, a frequent result of oil starvation.

Now that the head was off, the cylinder and piston face were visible.

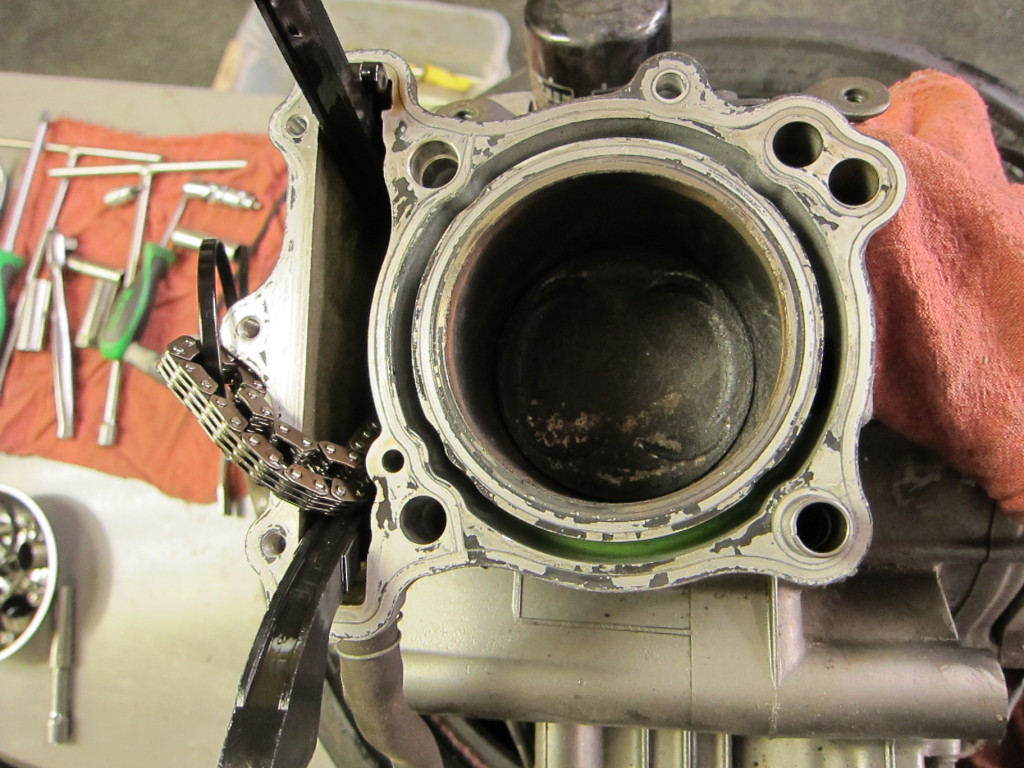

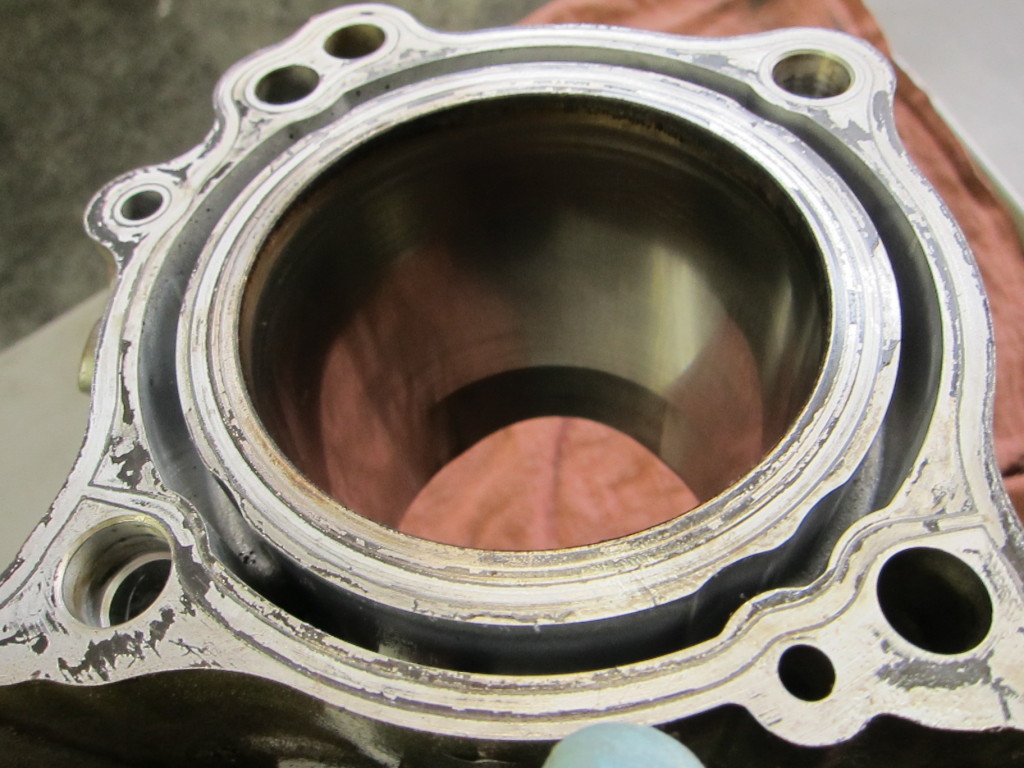

With the head bolts out, I was able to pull and inspect the cylinder.

The interior of the cylinder shows some scoring.

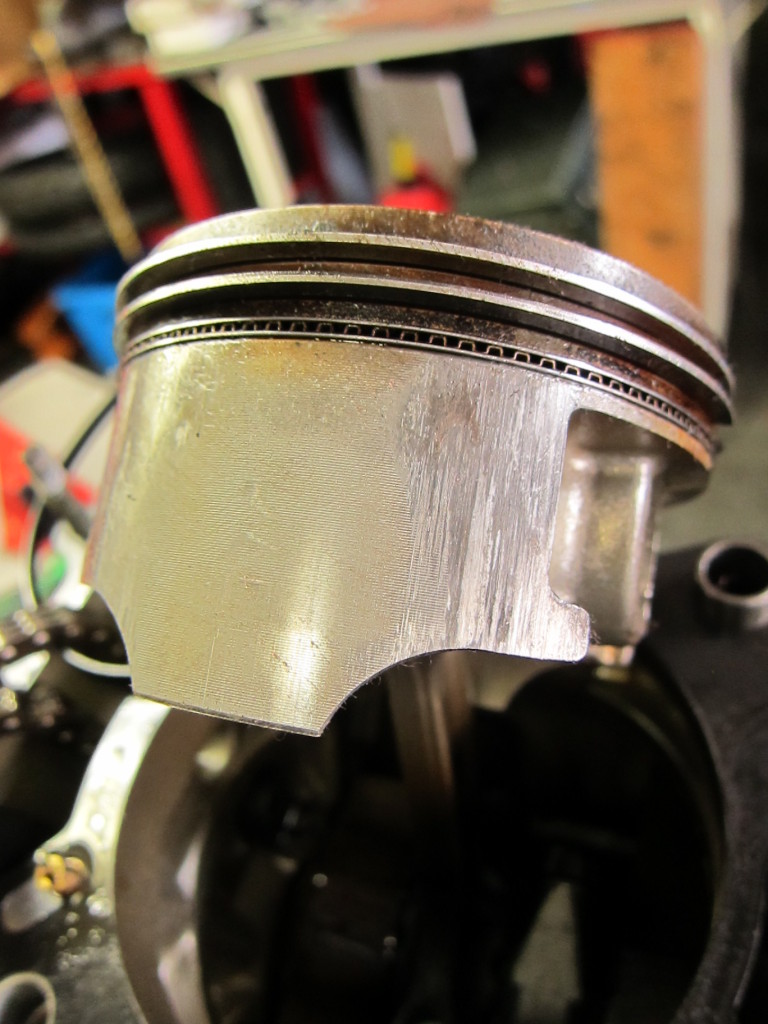

Normally, the piston rides up and down the cylinder in a thin film of oil. But when the oil is gone, there’s direct metal-to-metal contact as the piston begins to scrape and gouge the cylinder–and you can see the results.

The piston skirt had signs of scoring beginning to show as well. If the engine had not been shut off when it was, the gouges would have deepened in both the metal of the cylinder and the piston, eventually breaking one or both, or melting them together and seizing the engine.

I repeated the process with the other cylinder.

This piston, too, showed little to no damage, unlike the front cylinder’s piston.

The two rear cylinder camshafts were in fine shape, as well.

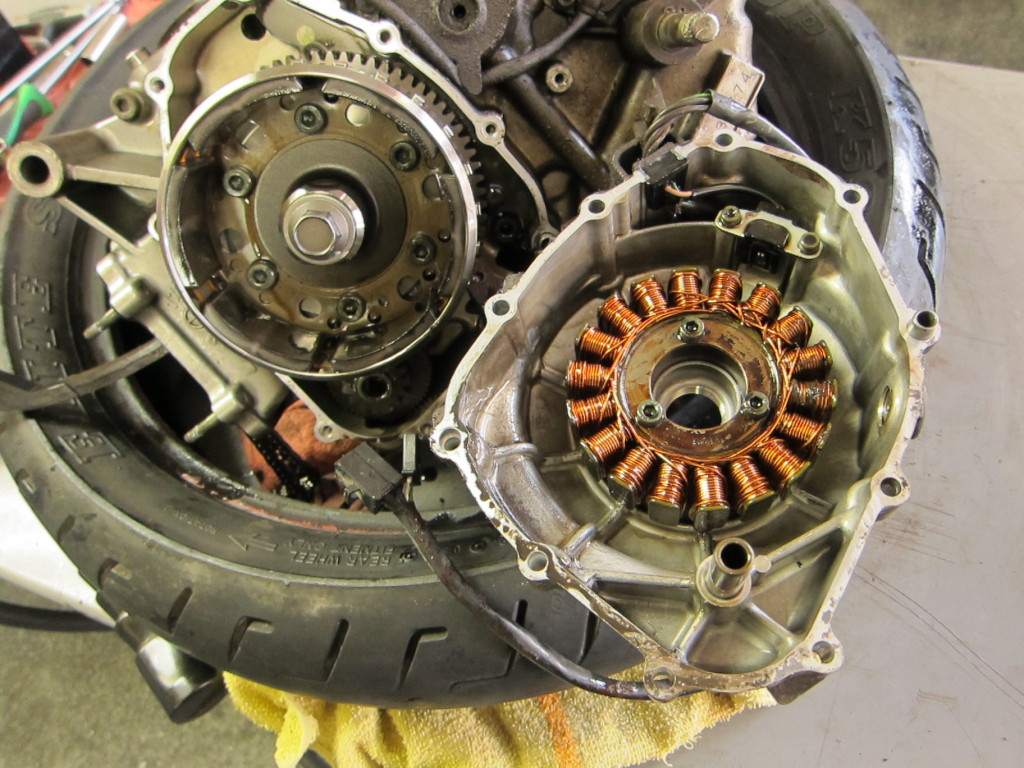

After the cylinders were removed, the stator cover was next.

With a bit of convincing with the deadblow hammer, the stator cover and stator came away, resisting as the flywheel magnets attempted to hold the stator in place.

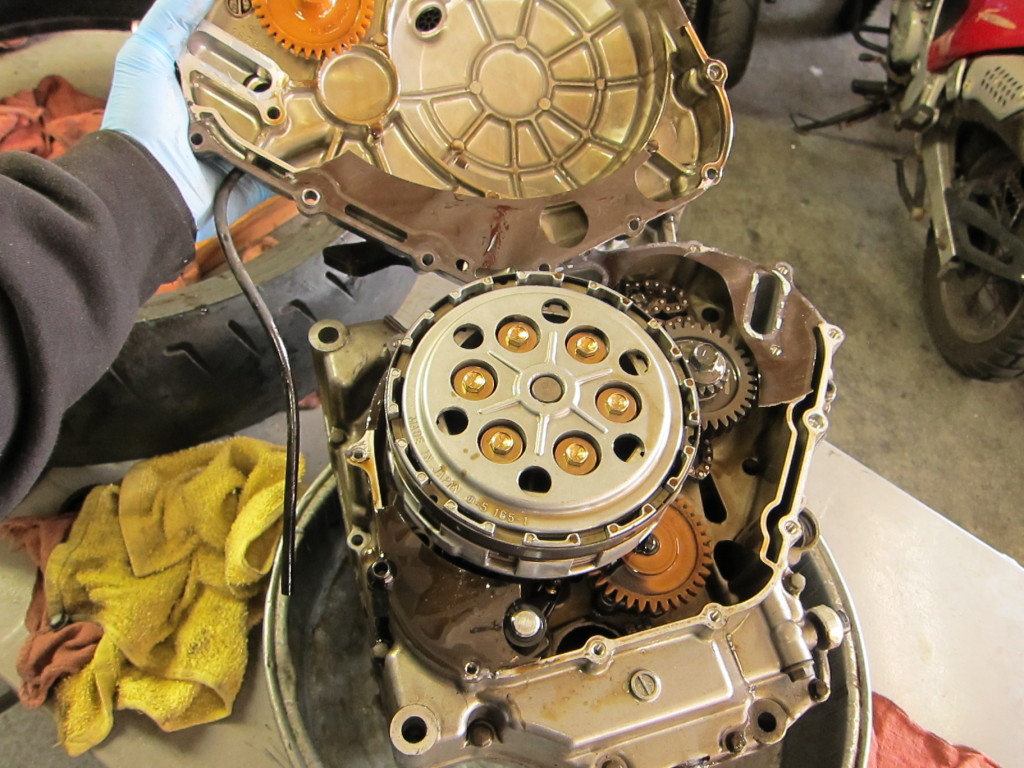

With the stator cover off, I flipped the engine over to take off the clutch cover on the other side.

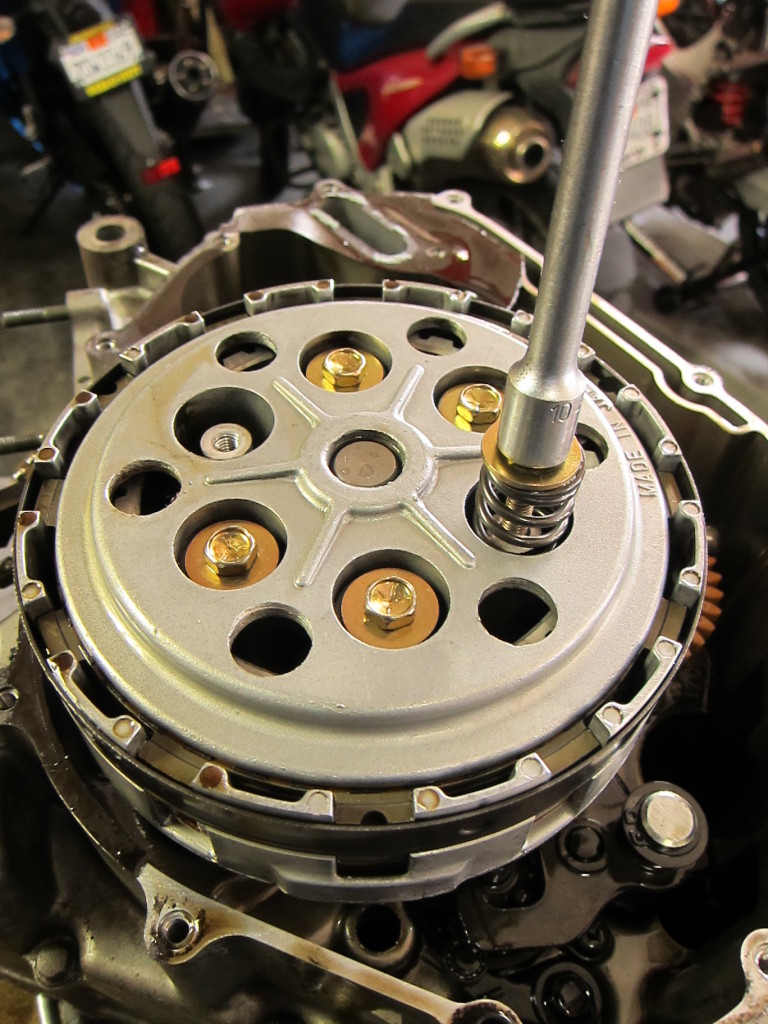

The clutch cover came off more easily, showing the clutch basket beneath.

And next, I unbolted the clutch basket itself and removed it.

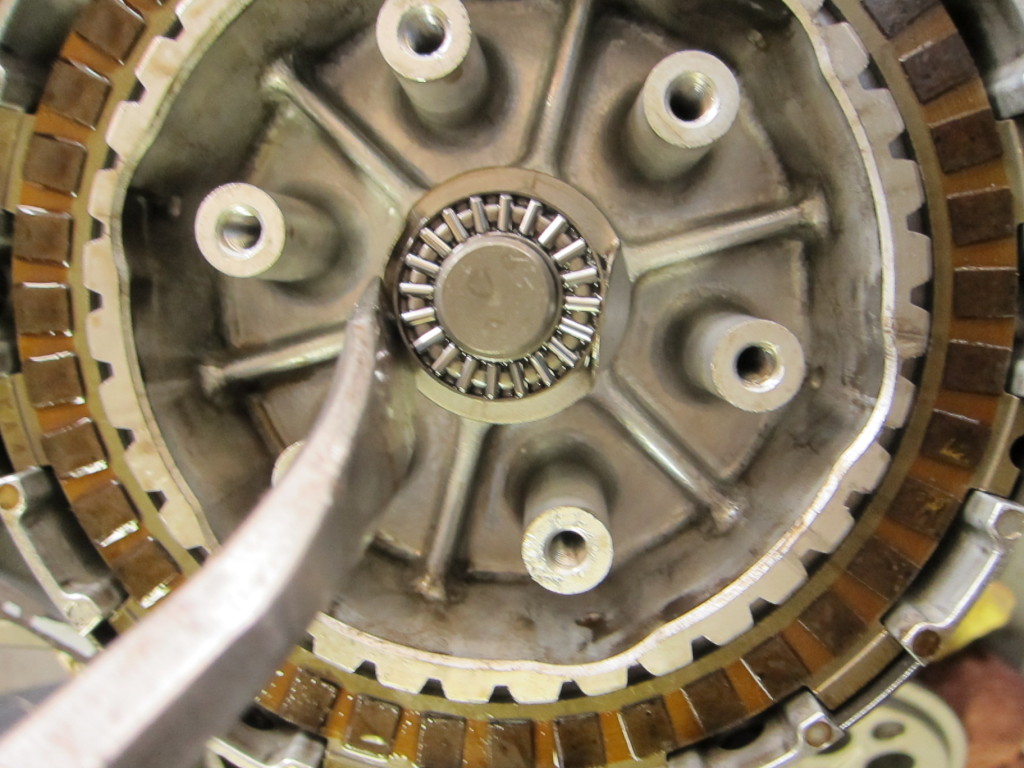

Now with the friction plates and steels out, the basket lay beneath. I pressed down the folded-up tabs of the washer holding the nut and friction bearing, and took them out.

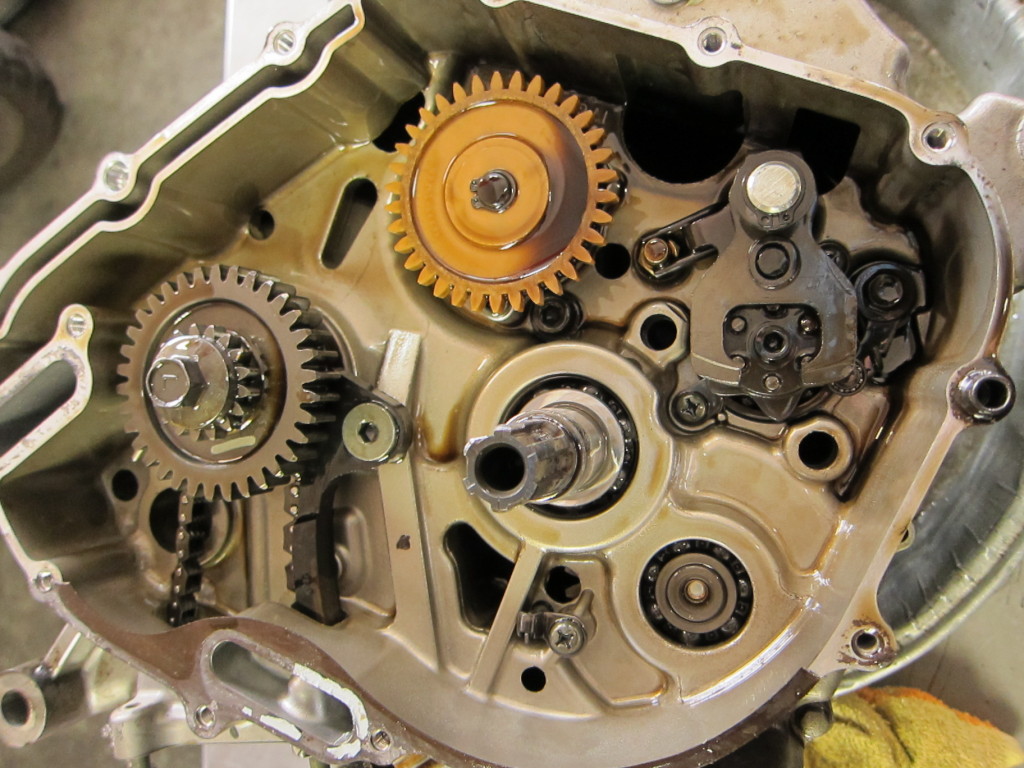

With the clutch basket gone, the deeper parts of the crankcase are exposed (the plastic gear is the oil pump gear).

With the top end of the engine (cylinders, valve head, camshafts and covers) apart, and the side covers, stator and clutch removed, it was time to get into the depths of the crankcases and see what damage had been wrought in the engine’s bottom end–which I’ll cover in the next post.